John meets me at the front gate of Melbourne University as students walk past, glancing back at him, not scared exactly, just surprised. The tattoos that completely cover his face are more vibrant than the dull green I was expecting.

“John?” I ask, pretending not to be sure that it’s him. I shake his hand, also completely covered in tattoos. As I thank him for agreeing to speak to me, I notice the whites of his eyes are stained red.

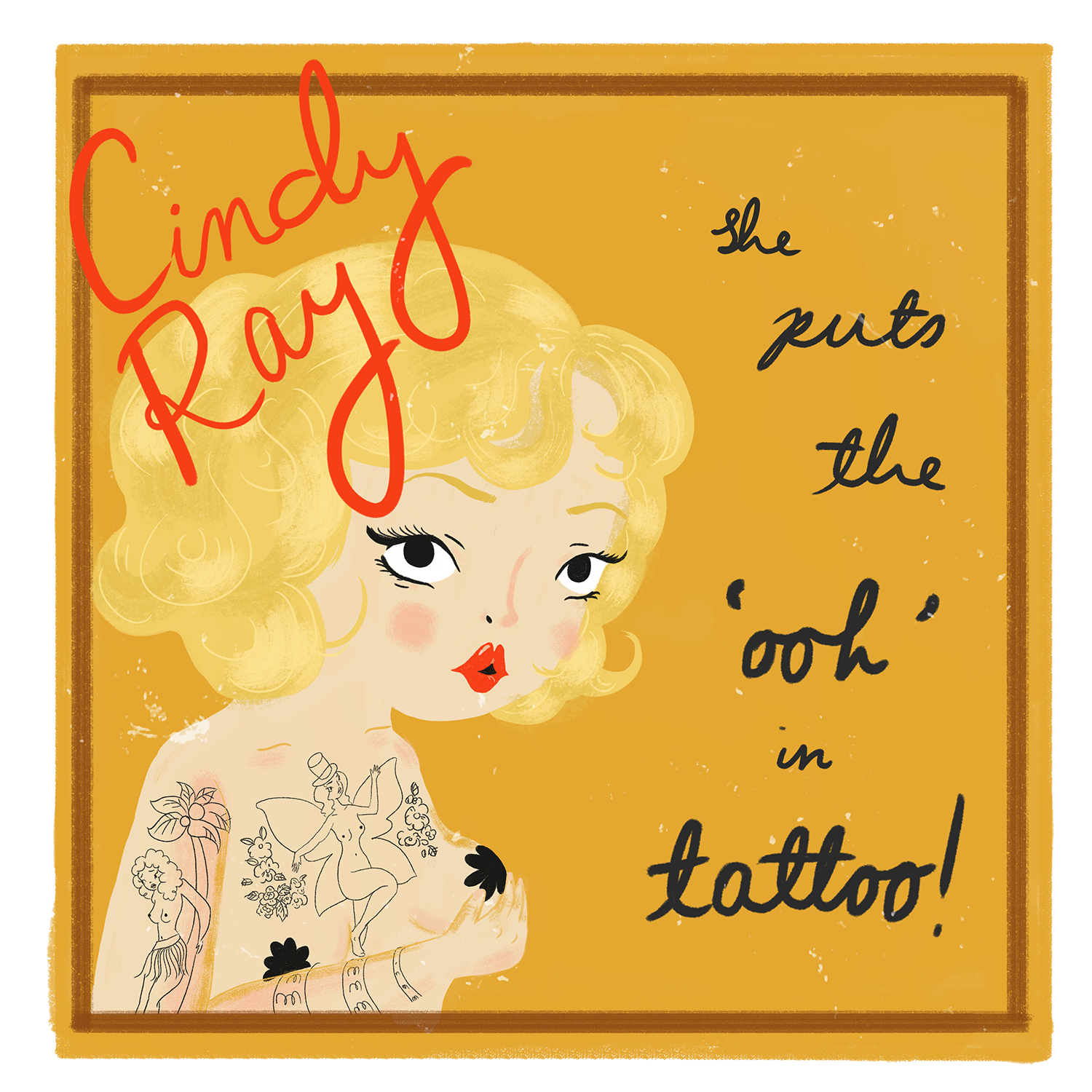

I knock on the door of Bev’s Williamstown home and a dog barks — it sounds like a big one. Bev opens the door and gestures for me to come in. A fat German Shepherd has its jaws around her wrist. Bev Robinson is famous for being one of the first women in Australia to cover the majority of the skin on her limbs and torso in tattoos. In the 1960s, she became known by the stage name Cindy Ray, “the lady who put the ooh in tattoo,” and travelled around the country, meeting or being displayed to scores of body-art enthusiasts. Following her career as a tattooed model, she became one of Australia’s first female professional tattooists. My tattooist friend tells me she’s world famous, one of only six people inducted into American tattoo historian, Lyle Tuttle’s Tattoo Hall Of Fame, and a legend in the industry.

"Git down Hondo!" She shakes the dog off; smiles. “Friendliest German Shepherd you’ll ever meet.”

The dog licks my hand until I believe her. We walk upstairs, and I notice that her tattoos are invisible under her sweater and jeans.

As I’m fiddling with my Dictaphone, John tells me he’s “got no folks, hardly did no work for my whole life. Mostly, I did drugs and alcohol and all that kind of stuff.” It becomes obvious that his bluntness isn’t hostile, just indicative of a preference for fact over feeling. He got his first tattoo because “he just did.” I ask him which one it was and he shows me a picture of an American-Indian woman on his arm. His reason for the image: simply that it “fitted into the right spot at the right time.”

I figure out pretty quickly that these tattoos, which cover 95% of John’s skin, aren’t going to tell me a story, or at least not the story that I came looking for. After seeing a few photos of John on the internet, I had come to him expecting to be told a narrative of obsession, or at least addiction, or, at the very least, that his body art symbolically mirrored aspects of his life. But ironically, John’s discussion of his tattoos makes them seem transitory — just decisions made in the moment as opposed to actions that would change the course of his life.

Bev became a single mother at 19. She struggled to find a steady income that could support her and her young son. Looking for any work she could get, she responded to an advertisement in the paper looking for a photographic model. Any respondent had to be willing to have their eyebrows shaved.

Events quickly spiralled. “Somehow it ended up I got talked into getting these tattoos so I’d make all this money—which I didn’t make—going on shows as a tattooed lady,” she tells me.

“Arseholes,” I say. She agrees.

Skin still raw with her first tattooing, Bev went home to her parents and “got her head blown off.”

John never minded the pain, which he describes as “a burning, charred feeling.” I look at his eyes, the vitreous humour bruised bloody pink. Having them tattooed didn’t hurt either, apparently. He points at his eyes:

“They put the needle in. There’s a certain way you gotta do it. You go too deep you get knocked out, you go too shallow, it just won’t take. It’s mixing colour amongst the fluid.”

His tattooed tongue makes his saliva look like blue dye. Briefly, I imagine all of John’s insides dyed blue. Tattooed inside and out.

Bev shows me the bands of roses around her wrists — her first tattoos. I ask her if she had any say in how her skin would permanently change. She didn’t. The folks who convinced Bev to be part of their plan wanted to get her tattooed and in the public eye as fast as possible. The scandal of being covered in tattoos was more important than the tattoos themselves.

“Do you regret it?” I ask.

“Yeah, well, probably today I wouldn’t have done the same thing... But anyway, you know, it’s just what happens.”

John tells me he spent four years with his favourite tattooist — “When you find a good one you wanna stick.”

She likes him because of his skin and even tells him he’s “one of the rare ones” because of how well colour takes to him.

It was only six years ago that he decided to "block in" his tattoos — to recolour the old and fill the gaps with new ink. This means the ink won't bleed and the images won’t be in danger of fading. His tattooist started from the feet, covering all of the hearts with names on them as she travelled upwards. The removal hurt more than getting them in the first place.

"You never get anyone’s names done. You end up with different names everywhere."

I asked Bev how she started out as a tattoo artist, a title she immediately rejects, preferring "tattooist". She tells me that her ex-husband, who was a tattooist, got into a fight one night and broke his hand. In order to keep the shop open and money coming in, Bev had to take up the needle. When she tells me about the financial want which made her Australia's first female tattooist, it gives me pause. Rather naively, I had assumed that to pioneer was to triumph unequivocally.

When I ask her what it was like to marry within the world of tattoo culture. She quips, "Big mistake."

"Never marry a tattooist?"

"Exactly"

Before I can ask how much his tattoos cost, John warns me off it.

"It annoys me,” he says of the question, "cos you know I can't put a price on it. I just enjoyed it and loved it."

He approximates, rather wildly, that four or five houses worth of ink is embedded just under the surface of about 95% of his skin. This seems unlikely, but nevertheless it is still a lot of money to spend decorating skin he doesn't intend to keep. "None of this is gonna be taken with me. When I go, it’s all getting left behind."

He tells me that he has written in his will that he wants to donate his skin to Canberra’s Belconnen Arts Centre.

"Look at some of the famous painters. They didn't take it with them."

I think about a tattooed husk hung on a hook in a glass case, being peered at by children, embalmed so as to never lose its colour. John figures it makes sense because the same arts centre has a 30,000-year-old section of tattooed skin on display. At first his fantasy is in some way funny, and then as he keeps on, it isn't, at all. I don't ask whether or not the centre is expecting his donation; he seems certain it'll happen.

"Cos I'm the only one like this in the world. You ain’t ever never seein' no one like me again."

The only money Bev ever made from her fame came from being paid by the letter to respond to the fan mail that was addressed to Cindy Ray. Most of her fans overseas still know her as Cindy, but sitting with her in the kitchen, dishes in the sink — as she coughs an aging woman's cough into her hands — she doesn't seem like Cindy at all. It's as if Bev Robinson and Cindy Ray are two different people sharing the same tattooed skin.

She tells me she's bloody sick of interviews. After declining last year to speak to a writer who was penning a book about tattoo culture in Australia, the same writer, in a live-talk, called Cindy Ray a "sideshow freak".

"And I thought, oh, lovely. But I don’t care."

I believe her. On hot days, she will sometimes venture down to the local supermarket with her arms uncovered. But you'll never catch her shopping in a skirt.

Hunting for a sound bite, I ask John if he could tell me in a sentence why he decided to cover his whole body in tattoos.

"I guess… I just got sick of bein' white. I wanted to be different from everyone else. Started my own tribe of coloured people. Decided to spend the last half of my life being coloured rather than being white."

I tell Bev that I tried to look her up on Facebook but couldn't find her. Turns out she avoids social media completely. “So I don't have to bloody look at meself. All these people leaving messages... I don't have to deal with 'em cos I don't have to.”

I laugh and say I know what she means. I'm lying.

"I'll be glad when I have Alzheimer's!" she says, cackling.

I thank them both.

Walk John to the front gate, my clean-skinned university peers gawking. Walk down Bev's stairs and let the German Shepherd lick my hand all over, careful to block the doorway with my leg so it can’t get out. I leave them both, and minutes later it’s already difficult for me to remember exactly what their tattoos looked like.

I'm reminded of how Bev, when I asked how she felt about being famous, responded with a snort of laughter and said, "I don't think of myself as famous, I'm just me."

I think, too, of how desperately John wants to be remembered, how ready he is to leave his skin hanging on a hook in a gallery, two empty holes where his red eyes used to be.

This story was created by the following people:

Editor: Jessica Yu

Writer: Brendan McDougall

Animator and Illustrator: Meg Gough-Brooks

Video Director: Angeline Armstrong

DOP/Video editor: Simon Gilberg

Composer: Esmond Angeles

Sound Designer: Dave Williams

Web Designer and Graphic Designer: Mellisa Hankins

Web Designer: Bradley Jackson

Special thanks to Bev Robinson and John Kenney for their time and stories. Thanks to Express Media, Copyright Agency and Signal Arts for their support. Last, but not least, thanks to The Lifted Brow for all of their help and support.

Story #1: SKIN DEEP

Skin Deep started as a casual conversation between friends. A bunch of us on the Betanarratives team were talking about getting inked at sixteen and forever after being asked how we’d feel about our “foolish decision” when we turned sixty. What started as a couple of laughs and aimless speculations about the future turned into a mini-social experiment in which we searched for sixty-year olds covered in tatts dating back to their teenage years and asked them how they felt about their ink today. These dining table conversations between the elderly and the young turned into a fascinating journey into the world of tattoo culture. We had the honour of interviewing, filming and illustrating Bev Robinson (also known by her stage name, Cindy Ray), a legend in the tattoo industry, who started off her career as a tattooed model and unexpectedly ended up as the first female tattoo artist in Australia. We also interviewed John Kenney, a man with tattoos scrawled over every inch of his body (including his tongue, eyelids and eyeballs). Both of them were fascinating subjects and both of their stories reminded us how tattoos—permanent marks in an age of impermanence—can represent the desire to control the uncontrollable.

The finished piece is not only a feat of beautifully sensitive and inquisitive writing on Brendan McDougall’s part but is also an all-consuming experience to interact with involving html5 parallax scrolling, mesmerising documentary style film (by Angeline Armstrong and Simon Gilberg), illustrated and animated re-interpretations of real-life tattoos (by Meg Gough-Brooks) and beautiful soundscapes (by Esmond Angeles). We hope you like it very much.

Love,

Jessica Yu

Editor-in-Chief of Betanarratives